In defence of complexity

Why is complex different from complicated and why do we assume that simple is the antidote to both?

A few weeks ago the very learned Andrew Last, he of Earnest Client Services Director fame, wrote a cracking blog about working with simplicity. Go read, its good.

In the spirit of vigorous debate, I’d like to offer a defence of why complexity matters.

The urge to simplify can be a really good thing, especially in a world that often feels like it is increasingly hard to decipher.

Products and services we love and use are often driven by a single purpose. Good web design is often simple web design. And the most memorable messages are often pointedly simple. There’s a reason the USP as an idea has survived in business and marketing. Some things that have proved powerful and effective in their simplicity:

- Google’s home page.

- Swiping right on a person you fancy.

- I ♡ NY t-shirts.

- £350m a week to the NHS.

Simplicity is a powerful force; it can be salient, emotive and seemingly natural.

Things are great when they ‘just work’. But a lot of effort will have gone into a thing being seamless. A lot of complexity will have been navigated to create that clarity of thought.

Simplicity has a lot of famous proponents too.

William of Ockham deployed his famous philosophical razor to demonstrate the law of parsimony (the simplest solution tends to be the right one). “Entities are not to be multiplied without necessity” said William.

The US Navy’s famous design principle ‘KISS’ was developed in the 1960s as a way of ensuring that systems and machinery could be repaired under combat conditions, in the event that an ill equipped team would need to repair it with meagre knowledge or supplies. It stands for “Keep It Simple Stupid”.

M&C Saatchi’s famous credo and best selling book, ‘Brutal Simplicity of Thought’, began life as a training manual for Saatchi employees (go read it, it’s wonderful).

So yeah, simplicity has some pretty famous people in its corner. And I’m not saying they’re wrong.

But, to me at least, it feels like simplicity has become a cult of sorts. And that’s not without its issues.

Swiping right on dating apps is marvellously simple, but it’s also a crudely reductive action. It’s compelling and highly addictive but it’s also effectively meaningless and belies the creep of market logic into our romantic lives.

£350m to the NHS might have looked bloody good on the side of a referendum campaign bus but it was, at best, a deliberate abuse of statistics and at worse an outright lie.

Google’s home page is probably the easiest way to search the Internet, but it’s also only one way to access the web. A single company controls 75% of global search traffic; for lots of people Google is the Internet.

None of these are original observations, but if we think about the way that all are united by their deliberate over simplification of things that are inherently complex then I’d hope we can begin to make the case for simplicity not always being straightforwardly ‘good’.

Simplicity is most often deployed, rhetorically and logically, as the answer to complex and complicated issues.

And creating simple distillations of complex problems is essential to designing effective strategies, but being conscious at what this distillation comes at the expense of matters.

All of the above examples are both complex and complicated.

But something being complex is not the same as something being complicated.

Complex systems have ‘moving parts’ (often lots) with emergent properties behaviour (e.g. the interaction amongst the parts of the problem or system contribute to it being greater than the sum of its parts). This means complexity isn’t a problem that can be solved, per se.

Complex systems have heterogeneous components at many levels, network like connections, feedback mechanisms and adapt to changing environments.

Whereas complicated systems or problems will always be solvable – even if they have a lot of moving parts – thanks to the application of tools, processes and raw computing power.

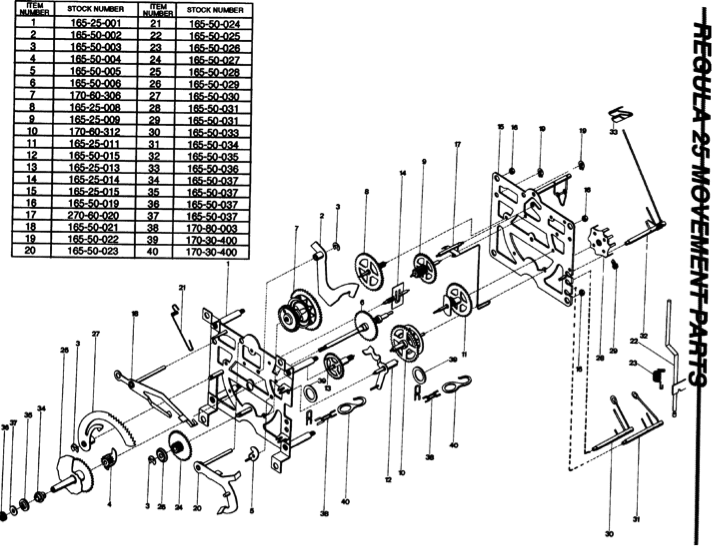

The best illustration of a complicated, but not complex, system is the humble workings of a clock – as illustrated by the lovely diagram below from cuckooclockologist.com (it’s my business how I spend my free time).

The working of the clock ticks some of the boxes for complexity: different components, a network like relation of its parts and it even has feedback mechanisms for controlling it. But a clock won’t adapt to its environment unless a watchmaker deliberately sets out to change it.

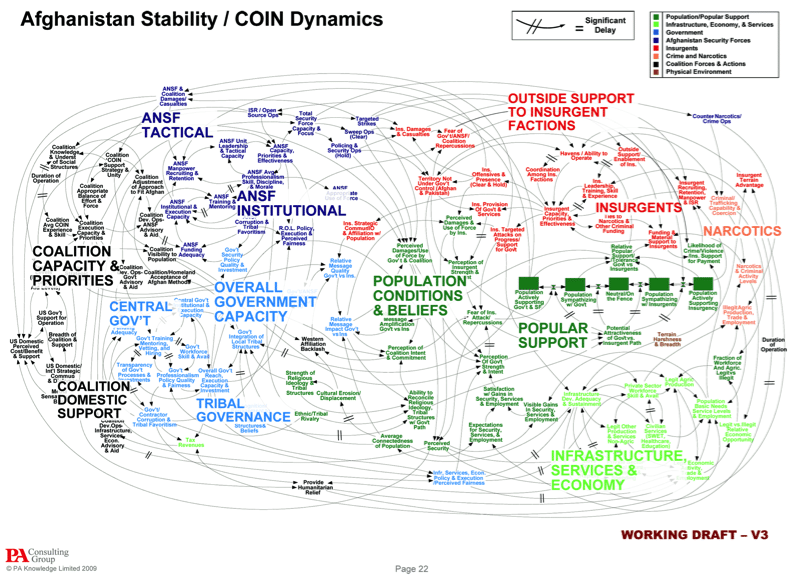

A classic example of a complex system is the US Military’s plan for stability in Afghanistan, as captured on a single slide by PA Consulting Group. “When we understand that slide, we’ll have won the war,” General McChrystal said.

The constituent parts of the situation mapped by this causal loop diagram add up to a problem far greater in complexity than any of the individual factors would predict. It is an intrinsically complex situation (as well as being highly complicated).

Facing up to complexity is a good thing; it houses nuance and subtlety, reveals insight and actual truth (rather than the appearance of truth or a kind of truthiness) through context and detail.

The issue with attempting to deliver simple solutions for complex problems is that complexity inherently deals in change – adaption, conflict and transformation occur because of the interrelation of moving parts. But there is a risk that overly simple solutions can’t effectively answer complexity without a loss of detail and true impact.

And ‘complicated’ isn’t inherently a bad thing, but it is an unattractive thing from a marketing or business standpoint. Complicated creates barriers to entry. Complicated creates inefficiencies and can diminish effectiveness. Complicated stops things from getting done.

In marketing strategy, we need to build simple solutions that help us manage complicated problems without whitewashing complexity. But pursuing simplicity dogmatically can obscure nuance and detail vital to meaning, understanding and context.

Something might be complex, but you’ve got a choice about whether or not you make it complicated.

Matthew Kilgour is a Creative Strategist @ Earnest who believes in reading stuff, remembering it and then doing interesting things.