How to stage an innovation intervention

Not to show off, but I’ve got a new iPhone. The newest iPhone, in fact.

***

[Header photo: Lorenzo Herrera on Unsplash]

It’s bigger, shinier, and more expensive than any phone I’ve ever owned. I have no idea how it works, where the parts came from or how I would go about repairing it when I inevitably sit on it / drop it out a window / hurl it into the sea to make some vague point about the disposability of modern existence.

I’ve had it for several weeks and I remain impressed by it. But I know that this will not last.

Most of us have become accustomed to living with, as Arthur C Clarke famously once put it: “sufficiently advanced technology [that] is indistinguishable from magic”, and it’s not just consumers being lured in by the shiny promises of the newest innovations.

Businesses are subject to a daily barrage of the latest applied technologies, innovations, and new ways of working, buoyed by a sea of articles with titles like ‘Top Tech Trends In 2019’ and ‘11 Industry Experts On What Your Workforce Wants’ and so on.

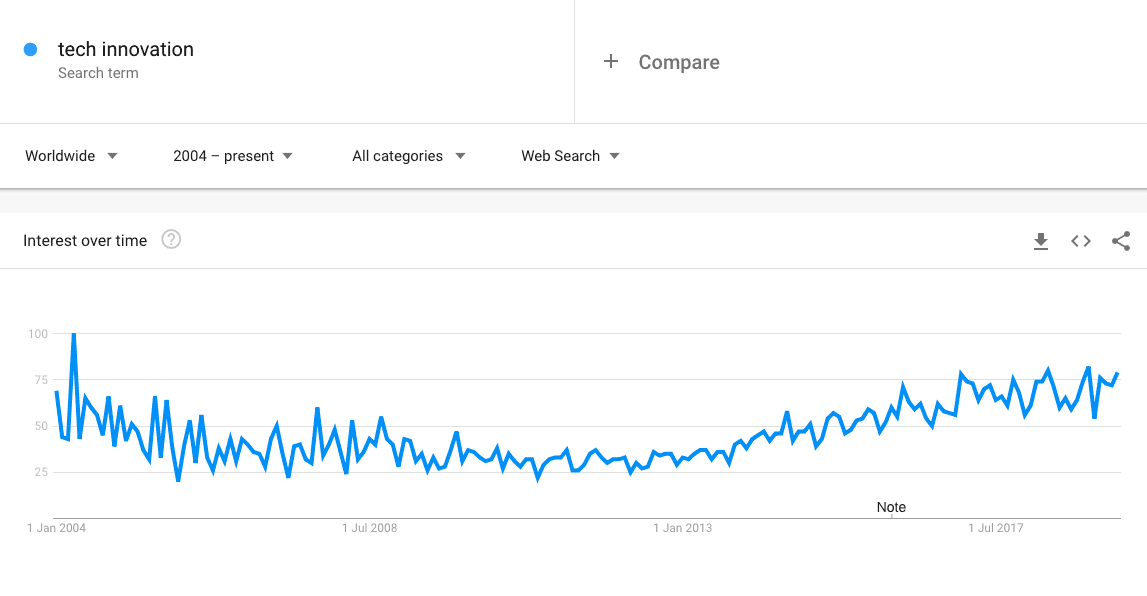

It’s not that innovation is a trend – even though the term itself has trended consistently upwards in Google search volume over the past decade — rather it is a fact of life for businesses but has become so ever-present that it’s stopped being, well, innovative.

And so, as I often do when contemplating the procurement and investment criteria for applied technologies, I reached for my nearest volume of poetry.

You may not have heard of Wendell Berry (no relation to Chuck), but Wendell led quite a life. Between dozens of volumes of poetry, eight or so novels and a Guggenheim fellowship, he has written about agriculture, the environment and people’s relationship with technology.

In 1987 he wrote an article for Harper’s magazine, ‘Why I am not going to buy a computer’. It’s a short polemic that, read from the vantage point of living in 2019, could sound a bit like a Luddite railing against the future.

In it, he shares nine standards for technological innovation that he intends to apply to his own work, and they are:

- The new tool should be cheaper than the one it replaces.

- It should be at least as small in scale as the one it replaces.

- It should do work that is clearly and demonstrably better than the one it replaces.

- It should use less energy than the one it replaces.

- If possible, it should use some form of solar energy, such as that of the body.

- It should be repairable by a person of ordinary intelligence, provided that he or she has the necessary tools.

- It should be purchasable and repairable as near to home as possible.

- It should come from a small, privately owned shop or store that will take it back for maintenance and repair.

- It should not replace or disrupt anything good that already exists, and this includes family and community relationships.

The simple logic of what Berry’s saying here is powerful: what does it cost and what do we gain? Are we controlling it, or will it end up controlling us? What is the wider impact of technology adoption upon our organisation?

Innovation is often presented as a silver bullet – ‘we can technology our way out this’ or ‘we’d be better if only we had more innovation’.

Berry achieved everything with simple technology. Prolific writing and contribution to many subjects, guided by simple principles and a herculean work ethic.

He understood innovation for what it was: a double-edged sword. Or, as my Nanna once told me: “a computer won’t stop you being an idiot, but it will make you a faster, better idiot.”

Berry’s simplest reason for not wanting a computer is that he did not wish to fool himself: “I disbelieve, and therefore strongly resent, the assertion that I or anybody else could write better or more easily with a computer than with a pencil.”

If you’re in the business of writing poems – or sending astronauts into space – a pencil is a mighty fine tool, but the rest of us have to figure out what to do with this double-edged sword we call innovation.

Which is why Earnest Labs has created these six simple ways to start innovating your B2B marketing.

Because let’s face it, who wants to live in a world full of faster, better idiots?

***

[Header photo: Lorenzo Herrera on Unsplash]